Why Wireless

Networks are Insecure?

Let's begin with the obvious: wireless technology is here to stay. What

is not so obvious is that for the foreseeable future it will be risky to

deploy. In this column we'll see why.

EVERYTHING YOU

NEED TO KNOW ABOUT WiFi IN 400 WORDS OR LESS

Well, here's a

tad of trivia that will move any high-tech wallflower to the center of

attention at any elite gathering. Question: When was the first Wireless

Network deployed? 1995 (WRONG). 1987 (NOPE). 1982? (huh-uh). The answer

is 1970. It was called ALOHANET (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ALOHA_network

), and it anticipated many of the core network

protocols in use today, including Ethernet and Wireless Fidelity (aka

WiFi ®).

If that piece of

intoxicating trivia won't produce a collective drool of golden sterlet

caviar, nothing will. If you can recite the trivia I provide in these

columns without making yourself look like you once had a bit part in a

Cheech and Chong movie, you'll make every A-list from Wall Street to

Hollywood. Trust me on this. Jeannie Caruso and I are even talking about

a converting this concept into a mini-series for the Discovery Channel:

“Survival IT: last nerd standing.” But I digress.

Basically, the flavor

of digital wireless technologies that we're likely to be most concerned

about in our enterprise are Personal Area Networks (PANs) and Wireless

Local Area Networks (WLANS). Both are widely used in business. Both are

saddled with insecurities.

THE ROSETTA

STONE AND WEP ENCRYPTION

Champollion showed that

comparing fragments of an understood plaintext (Ancient Greek) with an

encoded text (demotic or hieroglyphic) could be used to reveal the

correspondences . Hmmm, I wonder if there isn't an analogy somewhere out

there in cyberspace.

How's this? The WiFi

standard for encryption is called Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP). Since

it's built into the WiFi standard, it comes free with WiFi appliances.

(Even though it's free, it's overpriced.)

There are two common

varieties of WEP based on key length: 40-bit (standard) and 104-bit

(extended). However they're called 64-bit and 128-bit encryption because

the vendors want us to think that WEP is more secure than it is. The

additional 24 bits in both case comes from a 3-byte sequence that is

prepended to the key. This sequence is called an initialization vector,

or IV for short. I tell my clients that IV stands for “invasive vermin.”

The core algorithm of

WEP is RC4, but the implementation of WEP is fundamentally flawed: it's

both poorly designed and feebly implemented, but other than that it's a

nice piece of work☺. WEP is to wireless security what the Tacoma Narrows

Bridge is to landmark engineering failures. Both are case studies in how

not to do things.

The essence of the

weakness is the feeble way that the WEP designers approached the age-old

key distribution problem. Encryption requires the use of keys to obscure

the message. But somehow the keys, or means to re-generate the keys,

must be shared by sender and receiver. The WEP designers decided to

handle key management by sending the initialization vector and the key

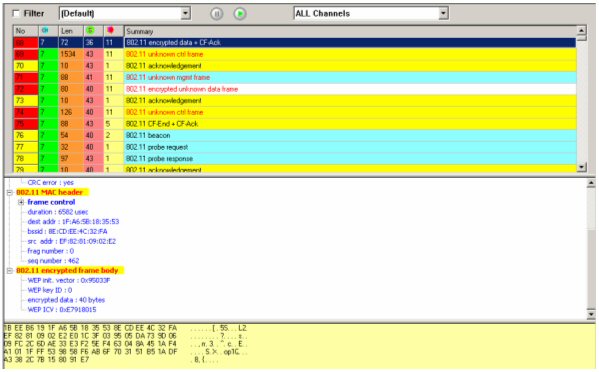

ID in plaintext in the management frame of the message sequence (Figure

1).

Figure 1: The Management Frame of an Encrypted WiFi Message. Note that

the WEP initialization vector, the WEP key ID and the 40-bit encryption

format are all broadcast in plaintext for any hacker sniffing the

wireless traffic to intercept.

Not content to leave

good enough alone, the WEP designers implemented a version of RC4 that

is hobbled. Whenever the middle byte of the initialization vector is all

ones (0xff), the byte of ciphertext pointed to by the first byte of the

initialization vector is exactly the same as in the message text - it's

just a matter of comparing the two (pieces of text (ala Champollion and

the Rosetta Stone). This is called a weak IV. In 'geek speak' we say

that a weak IV has a format of B+3::ff::X (where B is the byte of the

key to be found, ff is the constant 255, and X is irrelevant).

IS WiFi READY

FOR PRIME TIME?

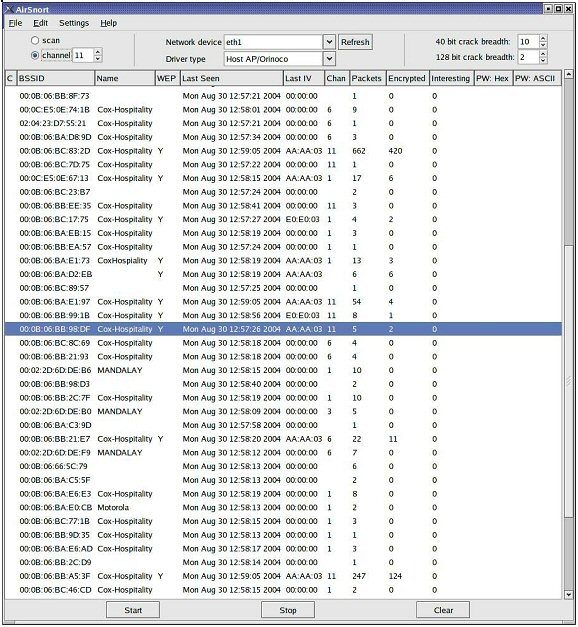

Take a look at Figure

2. This is a screen shot of casual sniffing of WiFi traffic from one of

my offices on Las Vegas Blvd. The column “BSSID” is the internal ID of

the wireless appliance. The columns of greatest relevance are “WEP” and

“Interesting.” When the entry for WEP is not “Y,” it means that the

wireless network isn't using WEP encryption, so everything is in

plaintext - email, Web pages, database commands, --- everything!

Interesting packets are those with “weak” IVs discussed above. The PW

columns would be passwords that are disclosed during the normal

interflow of packets. Bear in mind that this is only 45 seconds of

traffic that wafted into my office. What is more important, every

encrypted message from these wireless sites is vulnerable to attack -

and most aren't even encrypted!

Figure 2: Sniffing WiFi on Las Vegas Blvd with AirSnort. The column

marked “interesting” betrays the weak keys. A rule-of-thumb is that

wireless hacking tools require only a few megabytes of “interesting”

packets in order to break the key.

WiFi SECURITY

AND DIGITAL RISK MANAGEMENT?

Wireless is here to

stay. At the moment, however, it's radically over-deployed. This is in

equal parts a result of convenience and a desire to be perceived as

“current.” Unfortunately, recent legislation like Sarbanes-Oxley, HIPAA

and Gramm-Leach-Bliley presents a real-and-present-danger to executives

who underestimate the potential threat of insecure wireless. Given the

inherent vulnerabilities in WiFi, a good starting strategy is to assume

that all wireless traffic is printed and left in public areas for all to

see. If your organization doesn't mind if that traffic is read, there's

no problem. On the other hand...

This actually leads me

to a topic that comes up a lot in my consulting work. Wireless security

has less to do with technology than it does with risk management. CIOs

and IT CSOs typically understand this point. It's lost on most CFOs and

CEOs that I've worked with.

The fault actually lies

on the IT side of the ledger. IT executives and managers have

all-too-often tried to justify WiFi security (for that matter, all

computer and network security) to CFOs and CEOs by means of a technology

mandate. That's the wrong way to look at it. WiFi security is best

justified as a risk management mandate. Conceptually, digital security

of digital assets is no different than physical security of physical

assets.

Now that we've closed

most of our modem banks, WiFi has become the greatest security breach in

our organization. Eventually, WiFi will become as secure as LAN-based

communications. But until that time, it's incumbent on the CIO to focus

on the risk, not the glitz, if we're to safely control the growth of

WiFi so that the organization and it's customers remain both well-served

and secure.

So anyone may be

listening to your WiFi traffic. Remember, it's not paranoia if it's

true!

by Hal Berghel |

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()